" If we look at the myths, legends and oral traditions and at the cosmologies of the people of Oceania, it becomes evident that they did not conceive of their world in microscopic proportions. Their universe comprised not only land surfaces, but the surrounding ocean as far as they could traverse and exploit it, the underworld with its fire-controlling and earth-shaking denizens, and the heavens above with their hierarchies of powerful gods, named stars and constellations that people could count on to guide their way across the seas. "

Close your eyes and let the text written by the Samoan philosopher Epeli Hau'ofa resonate. This fragment demonstrates the unifying principles connecting, explicitly or implicitly , modern pacific artists like Mahiriki Tangaroa in subject matter and stylistic influences. However today these scattered island states are confronted with changes and challenges brought by commodification, modernization and globalization. The God of the Sea Tangaroa, caricaturally burnt on the retina of locals and tourists as Tiki memorabilia, is culturally revived as a vulgarized commercial commodity.

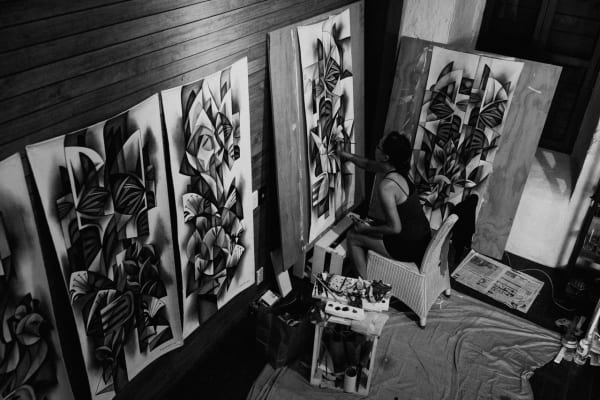

In her latest exhibition Earth, Wind & Fire, Irrespective of Place, shown at Bergman Gallery in 2019, Tangaroa indicates her concern for the way in which the Cooks Islands are handling the threat of globalisation, cultural heritage and climate change. Her artistic response captures the most subtle shifts in her mood towards the fragile changes in the state of the sky, wind, sea and trees. In short, the mixture of telescoped color schemes, conceptually layered geometry and subtle floral images function as commentary on the unresolved complexities of cultural identity, beliefs, social changes, religious colonialism and people's fading relationship with nature's four elements. So let her oeuvre's prismatic magic take you on a spiritual journey back in time right through the issues of the present.

The evocative visual legacy of the Pacific is being cannibalised to souvenir status by the standardised proliferation of Tapa, Tiki's and trademarks of the God Tangaroa. Selling mass-produced relics without transferring any spiritual power or epistemological connection reveals the irony of the idea of cultural authenticity. For the locals, those Tiki's are part of their uncertain "surrendered" identity, while for tourists they are an exotic decorative trophy. Fortunately, Mahiriki Tangaroa's concern for the disappearance of her cultural heritage has strengthened her urge to visually build on the remaining points of reference. In fact; the God Tangaroa is the catalyst for Mahiriki's artistic and personal journey. Although Tangaroa force is hard to objectify, the artist studies the Gods little known oral history, cuts the figures structurally and conceptually up into pieces, to later re-assemble them from different points of view into her visual statements.

The visual artist makes from cultural artifacts, forever primitivised or ethnographed, an avant-garde gesture, a provocative rather than appreciative act with stylistic consequences. To depict Gods in their entirety or truthfully would take away the faith in them, take away the veil of mysticity. Therefore, as a paternal guardian of reviving Cooks Island culture, she lets figurative remains of Tangaroa float in the echelons of the painting. Then the artist gradually breaks them down in geometric planes. These architectonic planes are in turn supported by (old) motifs, designs and symbols dedicated to customary arts such as Tattoo, Tapa and Pareu. It is as if Tangaroa is trying to save his/her own heritage from fading away into oblivion. As the Polynesian identity echoes in the metaphor of the "Ocean in us", Mahiriki points out that "Tangaroa is in all of us". Mahiriki gives Gods a vital presence, brings them into a human context, reconceptualising Cook Islanders identity in ways that transcend their heritage. Juxtaposing tourist cliches with intriguing cross-cultural constructions, the artist not only fills a cultural void but also challenges the stereotyped and romantic images of Cook Islands culture perpetuated by religious and western strategies of the colonial past. Each of the paintings is a visual feast catapulting you to a campfire where old stories, about the dangerous heights of the mysterious mountains, the spirits of the ever encircling sea, the expressive radiance of the fauna and flora, are told while dancing and eating.

The evolution of her artwork can be read as a metaphorical voyage, Tangaroa's journey, a voyage of the Cook Islands as a constructed nation and her own personal voyage as a driving force in modern Pacific art. Tangaroa's voyage, the mythologies surrounding the God, the visual fantasies it generates and the threat it still poses to the idea of Christian civilization have made from Tangaroa a superstar. A figure that is located at the heart of culture and ritual and yet seems to appear to us only in its perceptual nature. Therefore Mahiriki's ongoing dialogue connects and disconnects Tangaroa from the past and transfers the perceptual in the conceptual.

When looking at her paintings, the viewer fuses multiple views into a single image, reconstructing objects from dislocated facets, bringing to bear their conceptual understanding of those objects. Encountering her bold oeuvre transcends our sense of civilized experience, giving live to an all-encompassing presence which reconciles primordial feelings with the modern condition, the ominous with the monstrous. To give Tangaroa life through the painting from different viewpoints, the artist wants his/her representation, built up by metamorphosed objects of reference, to be in excess of the visual conventions inherited. This excess is marked by the lack of distinction between the foreground and background, the rupture of Tangaroa in various proportions and by the radical conversion of the Tiki-faces into different masks. A new language of facially shaped patterns are elongated towards motifs of flowers, Tatoo and Pareu.

Masochistic power symbols combined with symbols evoking the softening beauty of femininity question human beings my(s)thical origins of existence. Her art of cutting and pasting Pacific motifs of colors and shapes extend beyond the depiction of the face of Tangaroa. She accentuates his unknown visual identity into the rest of the canvas, where it creates a boundless meditation of spiritual presence. Additionally the sensuously created "natural" lighting has the effect of altering the forms in which the different points of view of Tangaroa are discriminated from its surroundings, by tone, value, contrast, proportion, repetition, or direction of movement to all other structures, but nonetheless related. The painting functions as an organic whole, it breaths, moves and sketches Tangaroa as intercessor between man, woman and unconscious forces. The structural fragmentation and formal complexity of her work reinforces the conceptual ambivalence of the God figure and affirms an inherent conflict of interest.

Her triangularised Tangaroa dangles between materialization and dematerialization, between figuration and defiguration, between masculine and feminine. The mixture of confluences disguise the negotiation between cultural pride and disgust while the liminality is the artist's reflection of a deep ambiguity of history and tradition. Continuity of inherited conventions and alien aesthetic correlations permits her to rediscover pictorial authenticity for herself. The God thus acts not only as a model but also as an instrument for confronting herself with the complexity of heritage and the audience with their stereotypical assumptions about the South Pacific.

Just like in other countries, and more specifically the Pacific islands, there are problems specific to our zeitgeist that requires our attention. Education levels are decreasing and there is a continuous depopulation accompanied by an increasing level of foreign labour. Technological progress is generating a cultural revolution and countless tourists are easily finding their way to the paradisiacal islands, leaving indelible marks on the demand for culture, the environment and its infrastructure.

The artist draws inspirations from the region's socio-cultural question marks and critically sets our priorities in order. Expectations about the reality of the Cook Islands are subtly tackled through the artworks visual structure and its corresponding narrative purpose. The constructive brushstrokes create a pictorial space in which opposing planes pull against each other, each containing the other, paradoxically, within the flat surface of the canvas. The small plane pulls up or down, away from or towards the lower edge of the overall rectangle. Other planes decide the direction of its force as they are added. Since each plane has a distinct, tangible location in depth, Mahiriki is pushing the spectator into the presence of a sculpture. This moving presence, accompanied by specific symbols and motifs, shows that her paintings talk about a specific place and identity. As a critical agent in the evolving nature of Cook Islands identity, her structural and narrative self-consistency is further indicated by her use of color. Each area of color, like each form, is integrated by balance and feeling. The colors are trying to comprehend the richness and depth of the Cook Islands generally endowed of land and sea. Her use of dialectic colour schemes are aggressive, sensuous and fragile but remain hopeful for the future.

Romantic earthy tones guide you through nature's sublime powers while the deep, dark colors become lighter in tone towards the edge. This strategy deepens a viewer's understanding of the three-dimensionality (place & space) in her paintings. Colors depict form and volume in her work and take the spectator on a historical trip, prophetically heralding the future.

There is in her visual work, a vitality of form, unnerving emphasis on the structural planes in architectonic sequences, the uncompromising truth to color, structure and symbols with a seemingly thoughtful adaptation of it. Her artistic evolution can be sketched through her relationship with analytical cubism, partly inspired by female abstract art pioneer Louise Henderson and Mr. Art New Zealand , Colin McCahon, and modern Pacific avant-gardism. Over the years, the artist has further dismantled the representational structure and shows an even stronger urge to dissolute composition and boundary perceptions. Her idiosyncratic use of colors, motifs, structural lines and spatial relationships offer sparse yet sufficient visual information. Instead of depicting objects from one viewpoint, the artist depicts subjects from a multitude of viewpoints to represent the subjects in a greater context. Topics related to the tensions between modernity, cultural heritage and the place of the spiritual in our contemporary world are deciphered by studying the symbolism, context, juxtaposition and (textual) interpretation.

In this sense, her trajectory is one of pushing the boundaries of the canon of Modern Pacific Art into unknown descriptive categories. In this pursuit, namely in a culturally cohesive way - the artist reflects a common sense of identity, place and time, Mahiriki is supported by the progressive art gallery, Bergman. Her journey as one of the leading and innovative figures within this elastic "movement" can be summed up briefly as an attempt to transcend the tension between the idea to be expressed through spiritual, natural and customary representation and the abstract principles of painting, photography and sculpture. As an artist, she embraces a modernist creed imbued with Pacific spiritualism, daring intellectuallism and European aesthetics. She challenges both Western and Pacific notions of art.

What is the connection between the way people relate to one another, their natural environment and cultural heritage? I have made it clear that English is a limited language when trying to understand and assess artworks arising from other parts than my own. Maybe it is because Mahiriki Tangaroa enhances ideas of semiotic reading, metaphor and significance through a restricted display of content. However, this is exactly where the excitement lies, the Cook Islands based artist delivers a challenging visual engagement that dwells less on the notion of representational space than on formal construction and concept. Purely preoccupied with the invention and arrangement of spaces, surfaces, shapes and colors, Mahiriki reminds us to focus on what we see instead of what we know. Her paintings offer a check on our perspective and asks the viewer to draw the line between the myths and realities that make up the Pacific. But essentially one keeps wondering what lies behind those masks and motifs.