Bergman Gallery Auckland

19 April - 13 May 2023

Artist notes / Everlasting emptiness

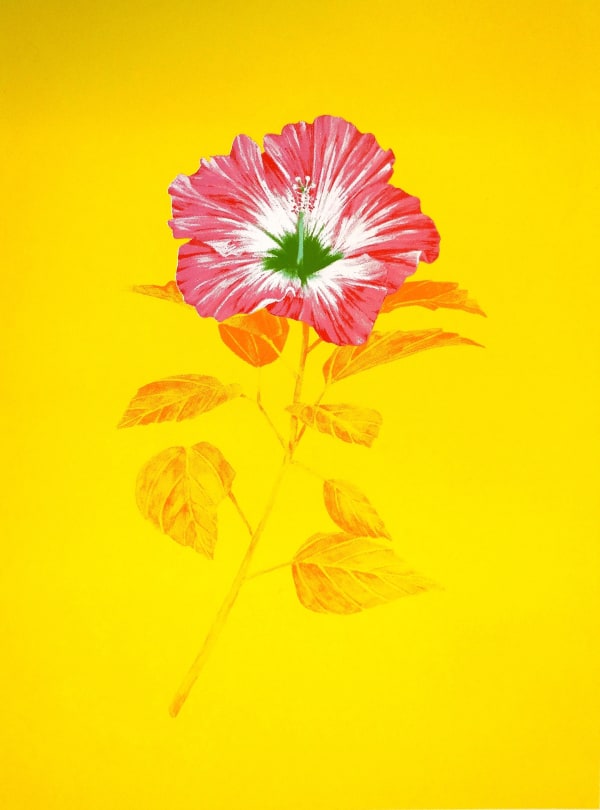

The Printed Hibiscus is an exploration into botanical study and floral fabric history, settling uncomfortably on the stylised hibiscus as it has come to represent / misrepresent the South Pacific.

Firstly, the hibiscus inevitably resonates with my life in Rarotonga (2011-2016) where most of the Island's gardens include at least one variety of hibiscus and where tropical floral prints are worn by local Cook Islanders and visitors alike. For such a simple subject, the project research became surprisingly complex. It began with the flower as a botanical specimen, exploring the intersection between humans and plants as an ethnobotanical subject, and finally expanded through my own personal and process-based experience.

The hibiscus motif is not discussed through its cultural use by indigenous Pacific communities but instead, references fabric design history, centred on its nearly ‘100 year old’ connection to Hawai’i triggered by a single photograph of my Grandparents in Honolulu from the 1990s. The focus became narrowed to the printed / manufactured hibiscus image that is recognised around the world through the ‘Hawaiian’ or ‘Aloha’ shirt.

[1] The origins of the patterns were certainly inspired by vibrant hand printed Pareu[2] with bold botanical designs seen in Tahiti in the C19th. However, the shirt design that came to be synonymous with Hawai’i, is traced to Japanese and Chinese tailors and merchants particularly, who adapted shirts made from their own fabrics[3] to include more Pacific subjects.

In an ethnobotanical sense, flora and fauna have been used in design to connect places and people for centuries. Symbolically, the common red Hibiscus rosa-sinensis (literally translating from Latin to Rose of China) is the National flower of Malaysia and the State of Hawai’i. In South China it is a symbol of happiness and prosperity. But its associative repetition in the South Pacific, onto brightly printed fabrics, means something else, especially when that branding was largely targeted to American servicemen and tourists flooding into the newly annexed state of Hawai’i.

Relative to this moment in time, I consider the possibility that these motifs repeated, over and over, may become simplified and meaningless, or as Andy Warhol commented on his repeated series, “the more you look at the same exact thing…the better and emptier you feel.”[4] But on the other hand, meaning and meaninglessness, becomes relative to context. For example, living or visiting an island such as Rarotonga places the tropical floral print into the very environment that inspired it. Perhaps this evokes a sense of connectedness with the natural environment?

Importantly, the Hawaiian-style floral shirt design has evolved and been reclaimed by many talented indigenous designers, intent on overriding the dominance of global manufacture with a significantly more authentic cultural resonance and production[5]. In the last two decades particularly, Pacific-motif branded fabrics have been made by indigenous Hawaiians, in a similar way to Rarotongan craftspeople selling hand dyed and printed pareu with designers such as Elena Tavioni in the Cook Islands whose TAV fashion label sells garments branded with Cook Islands motifs.

Toxic Appropriations

Those of us who have visited or lived in any South Pacific Island have possibly worn Hawaiian-style shirts, pareu or dresses as they have been embraced by many other Pacific nations. We have seen celebrities from Elvis in the early 1960s to Leonardo De Caprio and Johnny Depp branding contemporary and retro designs bringing the style into the mainstream. Dale Hope, author of a comprehensive book on the subject,[6] notes that the very first shirts made from Japanese kimono fabric of this style were worn by American servicemen in Hawai’i to show they were ‘off duty’. In my own family, once retired, my grandfather had a collection of Hawaiian shirts that he wore mainly during his time in Oahu which also signified a similar state of being.

More recently and much more caustically, the Pacific floral print has been adopted as a kind of perverse satire by the American far-right, anti-Government and pro-gun movement known as ‘Boogaloo.’ While divisions in the group range from white supremacists to some attending ‘Black Lives Matter’ and anti-vaccine rallies, the inclusion of the Hawaiian-style shirt with military attire and guns, may act to remind us how something as innocuous as a flower motif can be sabotaged. Historically this is nothing new. My Grandparents owned a beautifully carved coffee table from their life in Hong Kong and I still remember the horror of noticing what I thought was a Nazi swastika carved into each of its corners - only it wasn’t. My Grandmother told me about it being an ancient symbol[7] thousands of years before it was adopted as the Nazi party logo. I can only hope that the more toxic appropriation by this branch of the American far-right has little or no resonance in history. According to a New York Times article about the Boogaloo movement appropriating the Hawaiian shirt, “Meaning is rarely a fixed thing, which means that if something can be co-opted, it can potentially be returned to its original state of harmlessness.”[8] We know from history that this unfortunately, is not always the case.

So here, as with other potent symbols in nature (including the tiger), we might be reminded that our perception is shaped clearly by the time and place in which we find ourselves. These symbols in our lives in different contexts, don’t render themselves entirely ‘harmless’.

Regardless of these distortions and appropriations, I still remember hand screen and block printed hibiscus fabrics flying from clothes lines across the island of Rarotonga; I see it around the waists and torsos of indigenous people in the Pacific islands I have been lucky to visit, and I see it worn by those visitors attempting perhaps to ‘blend in’ as my Grandfather had done for many years in Hawai’i; and I see it here in Aotearoa reminding us as the colourful plants themselves do, that geographically and culturally we are part of the Pacific.

The hibiscus and a Tiger!

As the research of the hibiscus as both brand and cliché developed and drawing studies evolved, the final works came to include the tiger. While this may appear incongruous, it is intentionally playful and subversive, connecting to me personally and the broader story of the hibiscus motifs global history.

In the context of the exhibition, pairing the two presented an obvious solution to a number of convolutions in my research between fabric history (with Japanese and Chinese influence), ‘simple’ cultural symbols, and the weaving of particular past and present paradoxes. Outside pressure on South Pacific resources (such as strategic military placement and fishing rights) is as much a recurring theme of ‘East versus West’ in the media today as it was historically with opposing ‘superpowers’ bidding to assert their position within various Pacific islands[9]. How we view these symbols more crudely as power (tiger) and vulnerability (hibiscus), is not dissimilar to William Blake’s use of the tiger and lamb in his 1789 children’s poems 'Songs of Innocence and Songs of Experience’. I learnt the first verse at school:

Tyger! Tyger! burning bright

In the forests of the night,

What immortal hand or eye

Could frame thy fearful symmetry?

In this context, the dualism that the hibiscus and tiger may represent, could have more onerous connotations. But it is also oxymoronic - speaking of a deeper and less helpful culture of reductionism. I didn’t fully understand the poem as a child, nor did I understand until recently Blake’s personal agenda to subvert dominating doctrines by lacing his poetic imagery as less binary, more paradoxical.[10] Perhaps the point was to draw attention, (as many philosophies and indigenous belief systems have done before), to an understanding of coexistence and interconnectedness. That one cannot exist without the other.

This exhibition has been made during a war in Europe, the death of my last living Grandparent and a string of devastating natural disasters at home and around the planet. The divisions in our communities post 2020, have had an effect of collective anxiety and distrust. Across all information platforms we’ve experienced uncomfortable proclamations such as good / truth vs evil / lies at a time perhaps when we need to consider a more inclusive and productive wisdom and guardianship centred on the planet's future.

About the works / Ambience of disconnection

Botanical art as a painting practice is not only about capturing the essence of the plant, but for me, is about forging an intimacy with the subject itself. The early fabric designs evolved from this point, influenced by ‘Hawaiian’ shirt designers such as Alfred Shaheen and John Meigs. The hibiscus became stylised and simplified but missed something, so I returned to the research. The images began to merge with my own family heritage and the eclectic 1940-60s origin stories, popularised against a backdrop of tourism, fantasy and kitsch.

In the works Hibiscus tyger tyger, the tiger and the hibiscus link arms, bound by the pretty vines that smother vegetation throughout the Pacific. The ‘fearful symmetry’ of the tiger head, in this context is a form of balance and reflection, calling for a wider more inclusive view: in Chinese philosophy it’s yin-yang[11]; In Aotearoa, Kaitiakitanga[12] - speaking of the interconnectedness of all things which, as expressed, resonates for me personally.

The exhibition includes light work, and an exploration of different painted and printed mediums including digital print, fabric design production, screen prints and sign writing. In each, there has been a process of deconstruction of both the image and my own practice. The original botanical studies become slightly diluted through their different mediums becoming disjointed signposts. Where they lead seems unclear but speaks to me of an ambience of disconnection. The disconnect is not only from nature, but as we have seen over these few years - from each other.

With special thanks:

Ben Bergman (Director) and Benny Chan (Manager) of Bergman Gallery, Rachel Smith (writer), Mark Evans (fabric & catalogue design), Courtney Seng (ScreenCulture, New Plymouth), Virginia Winder (writer & hibiscus enthusiast), Geoff Budd (LFHQ Studios, Auckland) Nana of Hena Hena (Japanese Kimono tailor, Ashburton), my Great GM Darcy, Mac and Rita (Grandparents), Chauncey Flay (husband) and Darcy and Marcel Flay (children) … As well as to all my dear friends and visitors.

[1]The ‘Hawaiian-style’ shirt referred to in this essay is used to refer to a particular industry of shirt design and style that evolved out of Hawaii.The name ‘Aloha Shirt’ was first registered by Chinese Hawaiian merchant Ellery Chun in the 1930’s.

[2] ‘Pareu’ (also called Pareo) refers to a sarong-style fabric garment, worn by both men and women throughout the South Pacific. Originally made from tapa bark cloth it was adapted into light cotton introduced by Europeans to Tahiti.

[3] Hope, Dale, The Aloha shirt: Spirit of the Islands, Patagonia Works, Canada, 201 T6. Pp.49. Early shirts were reportedly made from imported Japanese kimono fabrics and Chinese cotton..

[4] Kass, Jason, et al. "Warholian Repetition and the Viewer’s Affective Response to Artworks from His Death and Disaster Series." Leonardo, 2018. Project MUSE muse.jhu.edu/article/684631.

[5] Withers, Sonya, Threading history through the Aloha shirt: From Hawai‘i to Aotearoa, 24 Jan 2018. https://blog.tepapa.govt.nz/2018/01/24/threading-history-through-the-aloha-shirt-from-hawaii-to-aotearoa/

[6] Hope, Dale, The Aloha shirt: Spirit of the Islands, Patagonia Works, Canada, 2016.

[7] “The word swastika comes from the Sanskrit svastika, which means “good fortune” or “well-being." The motif (a hooked cross) appears to have first been used in Eurasia, as early as 7000 years ago, perhaps representing the movement of the sun through the sky. To this day, it is a sacred symbol in Hinduism, Buddhism, Jainism, and Odinism. It is a common sight on temples or houses in India or Indonesia. Swastikas also have an ancient history in Europe, appearing on artefacts from pre-Christian European cultures.” https://encyclopedia.ushmm.org/content/en/article/history-of-the-swastika

[9] Referencing the recent controversial security pact signed between China and the Solomon Islands, April 2022. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-australia-61158146

[10]https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/jonathanjonesblog/2014/nov/18/william-blake-the-tyger-art-poem-tigers

[11]Referring to the “three basic themes [that] underlie nearly all deployments of the concept in Chinese philosophy: (1) yinyang as the coherent fabric of nature and mind, exhibited in all existence, (2) pyongyang as jiao (interaction) between the waxing and waning of the cosmic and human reals, and (3) yinyang as a process of harmonisation ensuring a constant, dynamic balance of all things.https://iep.utm.edu/yinyang/

[12] “Traditionally, Māori believe there is a deep kinship between humans and the natural world. All life is connected. People are not superior to the natural order; they are part of it. Like some other indigenous cultures, Māori see humans as part of the web or fabric of life. To understand the world, one must understand the relationships between different parts of the web.Kaitiakitanga is a vehicle for rediscovering and applying these ideas.”

Te Ahukaramū Charles Royal, 'Kaitiakitanga – guardianship and conservation - Understanding kaitiakitanga', Te Ara - the Encyclopedia of New Zealand, http://www.TeAra.govt.nz/en/kaitiakitanga-guardianship-and-conservation/page-1 (accessed 20 March 2023)